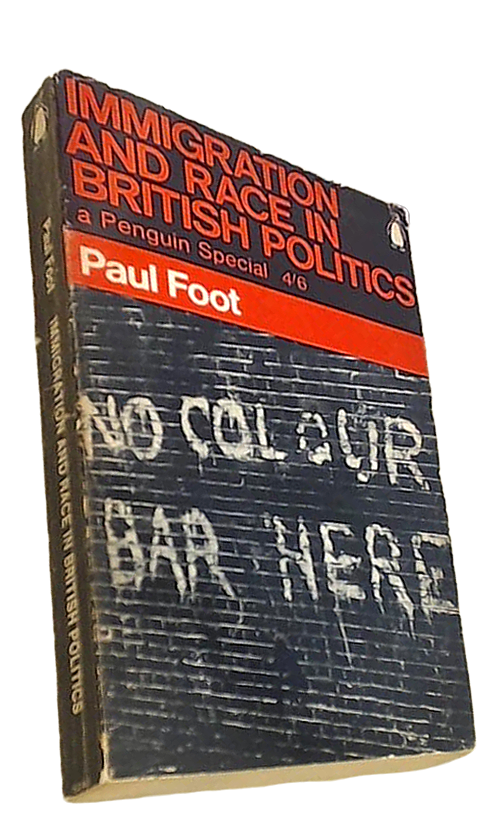

Within days of Harold Wilson’s victory in the 1964 general election, Paul was in contact with Penguin about writing a book on the politics of immigration.

The election was infamous for Peter Griffiths racist election campaign in Smethwick. His election address called for restrictions on immigration. He talked up dirty and overcrowded living conditions. He focused on a decline in moral standards and the need to make the streets safe at night. If Griffiths believed racist scaremongering would win him votes he was right. By fanning the flames of racism, Griffiths showed that you could win votes against the national tide that brought Labour to power.

The problem with post-war Britain was its massive labour shortage. But help was at hand. The British Empire had offered citizenship to its new subjects in return for the exploitation of their countries’ natural resources. ‘No one apparently,’ wrote Paul ‘foresaw the one crucial privilege which citizenship entailed – the obvious right of a British citizen was to come freely and live in Britain.’

For the Tory government after 1951, and the country’s labour- hungry employers, ‘this must have seemed a heaven-sent gift. The Commonwealth citizens came in freely – unhindered by the legislation applying to aliens. They cost the Government nothing.’ Neither government nor employers had to provide housing or language courses, or even additional school places for children. The migrants were left to shift for themselves. And while the numbers were relatively small at first – just 2,000 in 1953 – the steadily rising number put a degree of pressure on services that provided the right conditions for Griffiths’ campaign in Smethwick.

The Labour Party seemed incapable of countering Griffiths. Their candidate in Smethwick had been Patrick Gordon Walker, the sitting MP. His only hope, it seemed, was that the issue would go away, or that voters would get bored with it. Yet so vicious was the anti-immigrant campaign in Smethwick that Paul concluded even the most brilliant candidate would have lost.

Labour could of course have taken a different course, Paul argued – one of welcoming immigrants, providing help with housing and schools, urging trade unionists to accept immigrants gladly, recruiting them and fighting for better wages for all.

‘Mr Paul Foot is clearly a very angry young man’, wrote Norman St John-Stevas in his review for the Sunday Times. ‘He lashes out at virtually every political figure who has been involved in the immigration controversy.’ St John-Stevas was a new MP and would share the Conservative benches with Peter Griffiths. Meanwhile, the review for the Observer was written by another of the new intake of MPs, Roy Hattersley, Labour MP for Birmingham Sparkbrook. He did not like the book one bit, describing Paul as a zealot: ‘Since he believes only a tiny proportion of the politicians of either major party will do anything better than compromise with prejudice, he castigates them collectively and individually in a way which is often gratuitously offensive and occasionally ludicrously biased.’