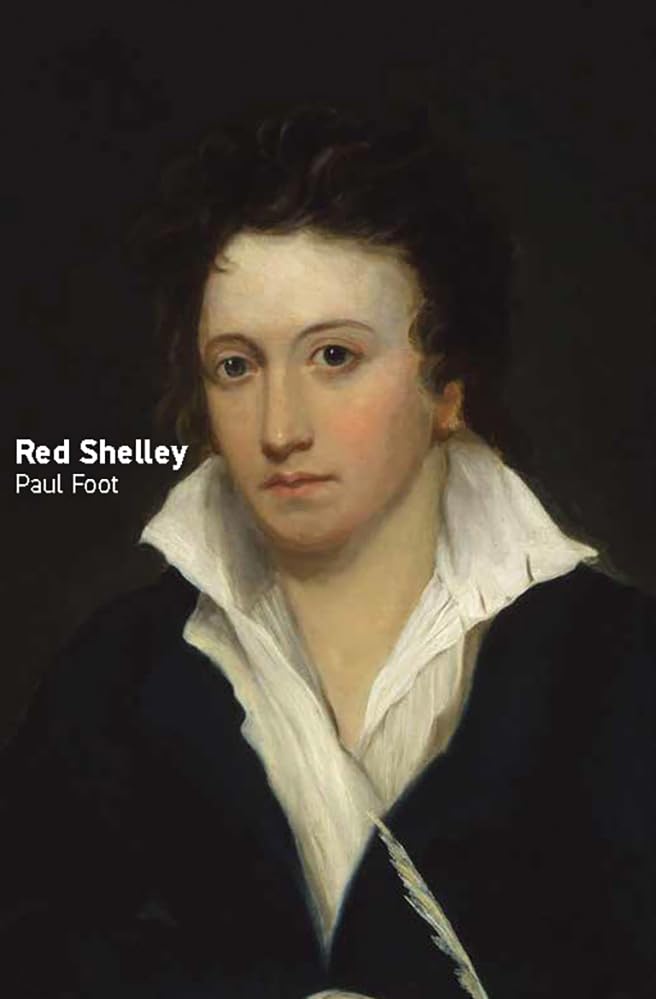

Paul loved poetry. From a very young age he had learned to recite poems out loud at his grandfather’s house in Cornwall, and no doubt Shelley was in the mix. But Paul was in his thirties by the time he realised what a wonderful poet Shelley was.

Shelley was indeed the finest of poets, Paul wrote in a long review of Richard Holmes’s biography: Shelley: The Pursuit, for International Socialism Journal. [Paul Foot, ‘Shelley: The Trumpet of a Prophecy’, International Socialism Journal. First Series, June 1975, and https://www.marxists.org/archive/foot-paul/1975/06/shelley.htm]

But he was also a relentless enemy of the power that came with wealth and, in Paul’s view, the genius of the poetry was inextricably entwined with Shelley’s convictions, inspired by the French Revolution and the writings of his mentor, the philosopher William Godwin.

Paul wanted to understand the poet who could write of ‘An old, mad, blind, despised and dying king’ in his poem ‘England in 1819’; who asked, ‘Who made terror, madness, crime, remorse’, in Prometheus Unbound; who got to the roots of inequality in ‘Song to the Men of England’: ‘The seed ye sow, another reaps; the wealth ye find, another keeps’; who understood, in Queen Mab, ‘War is the statesman’s game, the priest’s delight, the lawyer’s jest, the hired assassin’s trade’; who asked in The Revolt of Islam – in 1817 – the great feminist question: ‘Can man be free if woman be a slave?’

Red Shelley is not a biography in the conventional sense, but a book about the ideas central to Shelley’s thinking: his republicanism, atheism and feminism, and the radical politics of the Levellers. The longest section is devoted to the argument that runs through so much of Shelley’s prose and poetry: How could change come about, through reform or revolution?

The book was widely reviewed: Tribune and the Listener were much in favour, as was Marilyn Butler, a Shelley scholar, in the London Review of Books. She praised its emphasis on Shelley’s place in the world in the years after his death, ‘his underground influence as a political educator and his special reputation among Chartists, Fabians and other progressives’. [Marilyn Butler, ‘Death in Greece’, London Review of Books, 17 September 1981.]

The Telegraph was less keen – where was Shelley’s vegetarianism, the reviewer asked. And Richard Holmes, in The Times, found it ‘too tub-thumping, simplistic, ill-humoured, narrow’.

Radio and television programmes followed the book’s publication, including the rather wonderful Poetry and Revolution for BBC radio, with Christopher Hill and Tom Paulin, among a host of others. [Poetry and Revolution, BBC Radio 3, 20 September 1991.]

And The Trumpet of a Prophecy, an hour-long television programme, broadcast on Channel Four in 1987. It featured one of Shelley’s most famous and most misinterpreted poems: ‘Ode to the West Wind’. Often described as a nature poem, and considered a safe bet for school anthologies, it was not about nature at all, Paul told his audience. It was a poem about revolution and the revolutionary ideas that were blowing across the Atlantic from America. [Channel 4, The Trumpet of a Prophecy, 1 November 1987. ]

It was one of the poems Shelley wrote with a new collection in mind following the events of August 1819. Shelley was living in Italy when news reached him of the massacre at Peterloo. Boiling with indignation, he wrote the ninety-two verses of The Mask of Anarchy – ‘one of the great political poems of all time’, according to Paul.