Labour won the 1964 general election with a majority of just four. That election, announced Wilson, would be the start of a New Britain, one ‘forged in the white heat of a technological revolution’, after the ‘thirteen wasted years’ of Tory rule. Harold Wilson had then – and to some people still has – a reputation as a leader from the left of the party, not least because of his resignation in 1951 alongside Aneurin Bevan, the founder of the National Health Service, over the introduction of health charges.

Paul saw Wilson’s resignation as much more opportunist than principled. He went back through decades of speeches and writings, to Oxford in the 1930s and to 1945, when Wilson began his parliamentary career. He had done well in the post-war Labour government under Clement Attlee, but he was eclipsed by another aspiring MP, Hugh Gaitskell.

As Wilson’s star faded, he took ‘an increasingly oppositionist and Bevanite approach to the conservative policies of the Labour leadership’, wrote Paul. It was Gaitskell’s first budget that introduced NHS charges for false teeth and glasses and it was Gaitskell who became leader of the Labour Party.

But Gaitskell died unexpectedly in 1963, and Wilson was back in the running for leader. Later that year, his courting of the left paid off. He was elected leader, becoming prime minister the following year. The left MPs, including Paul’s uncle Michael, were enthusiastic, and the entire party rallied round. There were great expectations after so many years of Tory rule. Even Paul had felt optimistic that night in October 1964, as the votes were counted and a Tory majority of nearly one hundred was whittled down to nothing. ‘It was quite impossible for even the hardest revolutionary not to feel a rush of joy and even hope’, he remembered some years later.(Paul Foot, Pipe Dreams, Obituary of Harold Wilson, Socialist Review, June 1995.)

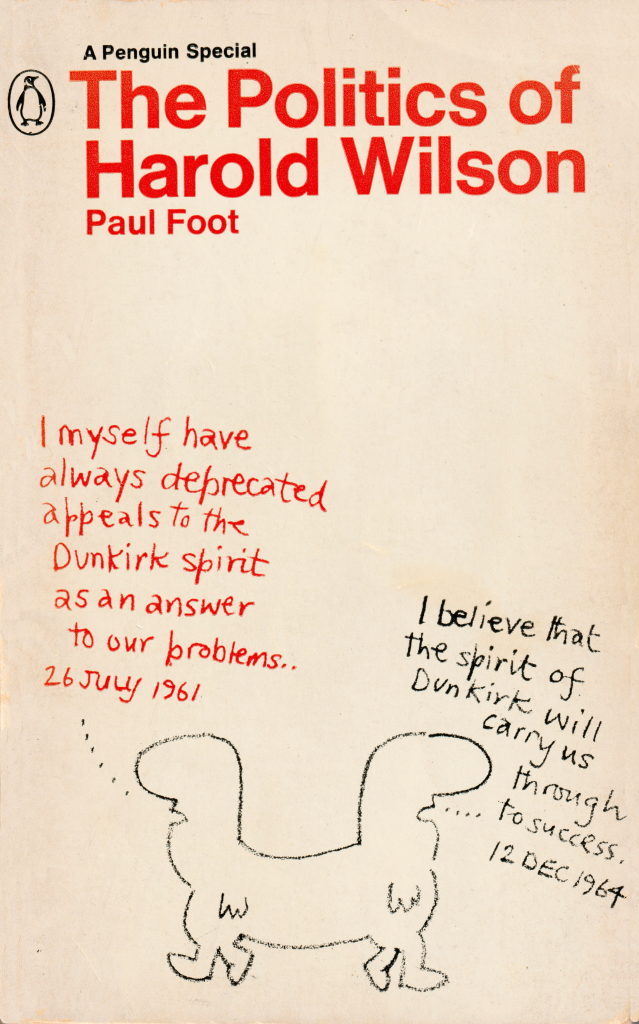

Paul’s portrait of Harold Wilson is not an edifying one. He is depicted as an opportunist and a man very often driven by panic. As the book cover says: ‘Wilson out of power was a magnificent rhetorician and political manipulator. Wilson in power (particularly since the 1966 election) has been a bemused figure, taking the easy way out, ditching principles, going back on commitments.’ Why? Paul argued that, lacking any coherent socialist theory, Harold Wilson was caught floundering.

Paul knew that the book’s publication was sure to cause a stir, and he offered the early proofs of the book to his Uncle Michael, who declined to read them, but he did promise to reply when it was published.

In a long review for Tribune, Michael pulled the book apart. ‘The politics of Harold Wilson are an extraordinary mixture of opportunism, improvisation, short-sightedness and resilience. Which is one reason for this book’, wrote Michael.

‘The politics of Paul Foot are an extraordinary mixture of first-class reporting, primitive Marxism, family wit and fantasy. Which is one reason for this review. Both may recover. The politics of Michael Foot are rejected in all quarters. Which is the reason for the general mess.’ [Michael Foot, ‘Michael Foot, on Paul Foot, on Harold Wilson’, Tribune 27 September 1968.]